Field research in the Greenland summer - what's that actually like?

26 September 2024

Photo: UHH/C. Steffens

This August and September, the MOMENT researchers were once again on Disko Island to take various samples, read out continuously recorded data on soil moisture, temperature and redox potential and measure greenhouse gas fluxes. What is it actually like to conduct research in an Arctic region? Christina Steffens sought to answer this question and accompanied and supported MOMENT researchers from the University of Hamburg in their work over 10 days. In a reportage, she describes her experiences, thoughts and feelings during this time:

Kangerlussuaq – Stopover on our journey. Claudia Fiencke has barely switched off the flight mode on her smartphone when it rings. On the other end: Disko Line, the ferry company that connects Ilulissat with Qeqertarsuaq on Disko Island. Fiencke is alarmed when she answers the call. “In Greenland, the journey rarely works out as planned,” she had told me beforehand, adding: ”You quickly learn to just take it as it comes.” The conversation lasts about 2 minutes, I listen anxiously. “There's supposed to be a storm tomorrow, so the ferry won't go tomorrow. They can't give any information for the days after that yet, but they have offered that we could go today. However, the hotels in Qeqertarsuaq are fully booked and we have to ask the Arctic Station,” summarizes Fiencke. The onward flight to Ilulissat has already been announced - it is due to take off on time. After a call to the Arctic Station, we know that we can arrive today - they still have space. We look for Jan Melchert and André Faust from the University of Cologne, who were on the plane with us from Copenhagen, and then things happen very quickly. Another call to the Disko Line and the new timetable is set - we arrive on Disko Island one evening earlier than planned.

Qeqertarsuaq, Disko-Island - The next two days are less stormy than forecasted, but still uncomfortable and rainy. As the sensitive measuring devices do not tolerate moisture well, we are not yet able to start the greenhouse gas flux measurements in the field. Before Easter, a container with various field and laboratory equipment was shipped from Germany to Qeqertarsuaq after complicated and time-consuming customs clearance. Fiencke and I used the rainy days to transport the field and laboratory equipment and measuring instruments needed for our work from the container to the laboratory and to the Red Hut. The Red Hut is located right on the edge of the study area in Blæsedalen. The path towards there is stony, with shallow ups and downs. After a short time, we come to a somewhat steeper descent and look out over a bridge. It allows us to cross the Red River. “Last year, after the snow melted, so much water came down the river that it destroyed the bridge,” says Fiencke, ”fortunately, the MOMENT researchers, who were on the island when it happened, were on this side of the bridge and weren't stuck in Blæsedalen. It took a few days before the bridge could be repaired.”

Today we have time for our way and I am amazed by the Arctic vegetation - so many lichens, mosses, grasses, creeping shrubs and flowers coloring the basalt rocks!

As we set off again from the Red hut, Fiencke says: “We're going back a different way, I want to show you something.” It was wet and cold, but our destination put us in a good mood. The forces of nature could be felt, heard and seen at a rushing waterfall on the Red River - the river at a dizzying depth below us.

After two days, the weather clears up - now the field work can really begin. After breakfast, well strengthened, we set off on the 45-minute walk to the Red hut and strap Licor's measuring equipment into the carrying devices. I decide to have my hands free and also strap the backpack with other field equipment and the day's food to the Licor, while Fiencke clamps her backpack under her arm. Wow - that's heavy... The carrying rack is good, the weight is shifted well to the hips, so that the back is relieved very well. But the shoulders hurt.

We set off cross-country in the direction of the measurement site over bumpy and rugged terrain, through waist-high willow scrub, over small streams and along a slope (just don't slip...). I'm glad I have my walking stick to give me extra support. It's an adventure and the landscape is breathtakingly beautiful, so the mood is good. A light, fresh breeze is blowing. I think: “It's a good thing it's only 6 degrees - I wouldn't be able to do this in 25-30 degrees Celsius.”.

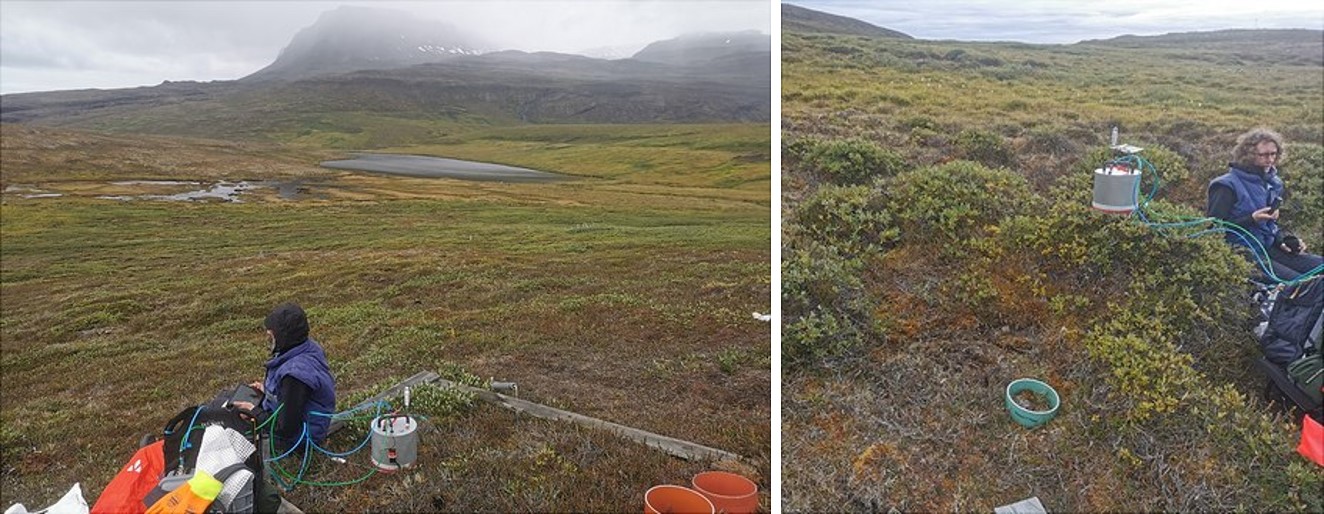

After about 30 minutes of heavy carrying through the terrain, we arrive at the first plot of transect 2 in the study area and start the measurements. Today we are measuring the three greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) with transparent and opaque chambers and with the help of two Licor analyzers. “Be careful not to touch the Licor during the measurement,” warns Fiencke, ”it is very sensitive.”

We also measure the soil moisture at two depths and the air temperatures at a height of 2m, soil surface temperature and the soil temperature at three depths (5, 10, 20 cm). Further, we determine the depth of the current permafrost table - here just a few decimetres (<0.5 m) belowground. The temperature decreases with soil depth and the temperature at a depth of 20 cm is sometimes only 0.6°C. “That's really exciting, in summer it's warmer at the top; when winter comes, it reverses and the soil is coldest at the surface,” says Fiencke. We work our way down the slope from one plot to the next and the short distances are surprisingly easy with the weight on our backs.

Towards the end, we have to go uphill once more and my strength starts to wane - steeply uphill with around 18 kg of luggage on my back - I have jelly in my knees. With the goal firmly in sight and with willpower, I arrive at the top totally exhausted, take a short rest and at this moment feel the greatest respect for all my colleagues who have been carrying this heavy Licor through this uneven terrain for weeks or even months. I already don't feel like it anymore. I lift my eyes and have a wonderful view over Blæsedalen. It's so quiet and peaceful and so breathtakingly beautiful - and I understand. Yes, carrying that heavy luggage is really exhausting, but the view is always a real treat for the soul - it just feels good.

In the evening, my shoulder hurts and the muscles are quite tense. “I hope my shoulder recovers quickly,” I think, standing under the hot shower and then treating the tense muscles with a heat pad.

The next day, we plan to go further. “The weather is so nice today, we'll make the most of it and go to transect 3 behind the moraine,” says Fiencke. I'm worried that this day will be even more strenuous and wonder when my body reaches its limit. Surprisingly, I quickly get used to the weight on my back. Yes, it's incredibly tiring, but today I don't have jelly in my knees at any time - and my shoulder is much better too! We walk for about an hour from the Red hut with the heavy Licor on our backs before we reach transect 3. In between, we take a short break on the moraine to reward ourselves with another fantastic view in all directions after the strenuous climb.

After a short measuring time at transect 3: my feet are cold, today the surface temperature is lower at only 5-6°C, but the weather is great and the view is again full of new impressive landscapes. The day is long - but the mood is good.

In addition to the measurements with closed chambers- today only with the opaque chamber due to time constraints - we also take undisturbed samples of ~4 cm height from different soil depths and place them in a jam jar (microcosms), which we then seal. Fiencke wants to find out at what soil depth the soil gases are produced or taken up. Enthusiasm spreads - the measuring method works and shows clear differences between the individual soil depths.

Today's field day ends at the alluvial soils in the Red River, and then after a long but successful field day we head back down the long, hilly, rocky, rough yet beautiful route to the Red Hut and then to the Arctic Station.

The next day is a laboratory and office day due to rainy weather. Time to prepare for the laboratory work - because in addition to the gas flux measurements, we have also taken soil samples and these are to be analyzed for various parameters in order to find out which of them influence greenhouse gas emissions. And time to nurse our tired muscles, because the next day we're off into the field again with the Licors, this time to Transect 1 and the “Hummocks”.

When we return to the Arctic Station after this rather chilly day, we are greeted by our colleagues Lars Kutzbach and Carolina Voigt, who arrived during the day. Over the next few days, Kutzbach and Fiencke will among others be working together with students from the University of Copenhagen.

I now have the opportunity to accompany Voigt in her work. I don't want to freeze again - so this morning I put on a few more socks and some extra ski underwear and help Voigt with her sampling along transect 1. We take soil samples on the upper slope under lichen and heather vegetation and then enjoy a lunch break in chilly but sunny weather with a great view over the valley.

This is followed by a third sampling on the middle slope. Now, we hurry, because suddenly the weather threatens to change. We have just finished when the first sleet falls, which shortly afterwards turns into rain. An icy wind comes up, the clouds move deep into the valley and the temperature drops down to only just above freezing. We quickly pack up our things, divide the heavy soil samples between the two of us and make our way back.

Over the next few days, the weather remains rainy with clouds hanging low in the valley. That's why Voigt and I take a lab day and collect roots from the soil samples to homogenize the latter for laboratory incubations. Voigt wants to find out how the CO2 and CH4 fluxes from different soil depths and under different vegetation are affected by different controlled temperature and humidity conditions in the laboratory. Collecting the roots from the soil sample is very tedious. We use the time for in-depth discussions on our scientific questions.

This lab day is also my last full day on Disco Island. To say goodbye, we first go for a tea made from local plants in the Kuannit Art Café in the evening and then head to the Blue Café for a last nightcap.

“Despite the strenuous, exhausting field work, the Greenlandic landscape with its views of icebergs is one of the most beautiful places to work in the world,” enthuses Fiencke. And I can only agree.